Perceptual Straightening of Natural Videos

Video is an interesting domain for unsupervised, or self-supervised, representation learning. But we still don't know what type of inductive biases will enable us to best exploit the information encoded in the temporal sequence of video frames. Slow Feature Analysis (SFA) and its more recent cousin Learning to Linearize (e.g. Goroshin et al., 2016) attempt to learn neural representations of images such that a trajectory spanned spanned by the sequence of transformed video frames satisfies a desired property, such as slowness or linearity/straightness. Whether or not the brain employs similar principles to learn representations is a fascinating topic.

Computational neuroscientists showed examples where representations learnt by the brain are consistent with the slowness principle (see e.g. Franzius et al, 2007). Brand new work by Eero Simoncelli's group suggests that the brain's representations are also consistent with the straightness principle:

- Hénaff, Goris and Simoncelli (2019): Perceptual straightening of natural videos, Nature Neuroscience pdf

This work is in fact a culmination of some great work by the authors over several years on developing the techniques that eventually enabled this study.

Straight representations

As you play a video, the frames of the video span a trajectory in pixel space. This trajectory is usually very complicated even for videos representing relatively simple actions. Imagine a video scene with he camera slowly panning over a static texture, such as a field of grass, at a constant speed. Despite the video appeaers conceptually simple and predictable, the trajectory of individual pixel values is highly non-linear and crazy: most pixels abruptly change their color from one frame to the next.

Instead of representing videos as sequences of frames in pixel space, we would like to map frames into a representation space, such that the trajectory behaves a bit more normally and predictably. For example, it makes sense to hope that in representation space the trajectory is straight or linear, meaning that it has a small curvature. If a trajectory is straight, it also means that linear extrapolation from the last couple points to the future works well.

Imagine we have a sequence (of frames) $x_t$. We map this into a representation space via a nonlinear mapping $f$. We can measure the local straightness of such representation by calculating the angle between the difference vectors $f(x_{t+1}) - f(x_{t})$ and $f(x_{t}) - f(x_{t-1})$. This angle is given by:

\begin{align}

\cos\alpha_t = \frac{(f(x_{t+1}) - f(x_{t}))^T(f(x_{t}) - f(x_{t-1}))}{\|(f(x_{t+1}) - f(x_{t}))\|\|(f(x_{t}) - f(x_{t-1}))\|}

\end{align}

The closer this value is to $1$, the straighter the sequence $f(x_{t-1}), f(x_{t}), f(x_{t+1})$ is locally. One can measure the straightness of the whole trajectory by averaging this local measure of curvature across time. It's worth noting that in high dimensional spaces, straightness is difficult to achieve. A $\cos\alpha$ close to $1$ is a very rare. Under Gaussian distributions, two randomly chosen vectors will be perpendicular to one another, yielding a cosine of $0$. So, for example, straight trajectories have an almost $0$ probability under a high-dimensional Brownian motion or Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) process. As slow-feature analysis can be seen as learning representations that behave roughly like OU processes (Turner and Sahani, 2017), SFA would not, by default, yield straight trajectories. If one would like to recover straighter trajectories, we need stronger priors and constraints, such as $k$-times integrated OU processes. See also (Goroshin et al., 2016) for another approach to recover straight representations.

Measuring Perceptual Straightness

When we train our own a neural network, we can of course directly evaluate the straightness of learnt representations. But ho we strudy whether the representations learnt by the brain exhibit straight trajectories or not? We can't directly observe the representations learned by the human brain. Instead, Hénaff et al (2019) devised an an indirect way to measure the curvature, i.e. infer it from behavioural/psychophysics data. Their approach relies on ideal observer models for a certain perceptual discrimination task: they infer perceptual curvature from data about how accurately subjects can differentiate between pairs of stimuli.

Here is how to intuitively understand why the approach makes sense: We assume that whether or not a human is able to discriminate between two stimuli, when flashed for a fraction of a second, is related to Euclidean distance in the person's representation space between the reprsentations of the two stimuli. Now, if you take a triplet of stimuli (video frames) $A, B, C$ and measure the pairwise distances $d_{AB}, d_{AC}, d_{BC}$ between them, you can establish the straightness of them as a sequence: if the sequence is straight, you expect that $d_{AC}\approx d_{AB} + d_{AC}$. On the other hand, if the sequence is not straight, you'd expect $d2_{AC}\approx d2_{AB} + d^2_{AC}$ to hold instead. So, if we have a model - called a normative or ideal observer model - that can somehow directly relate Euclidean distances in representation space to perceptual discriminability of stimuli, we have a way to experimentally infer the straightness of representations.

For more detailed description of the psychophysics experiments, data preparation, and the ideal observer model, please see the paper.

Results and Summary

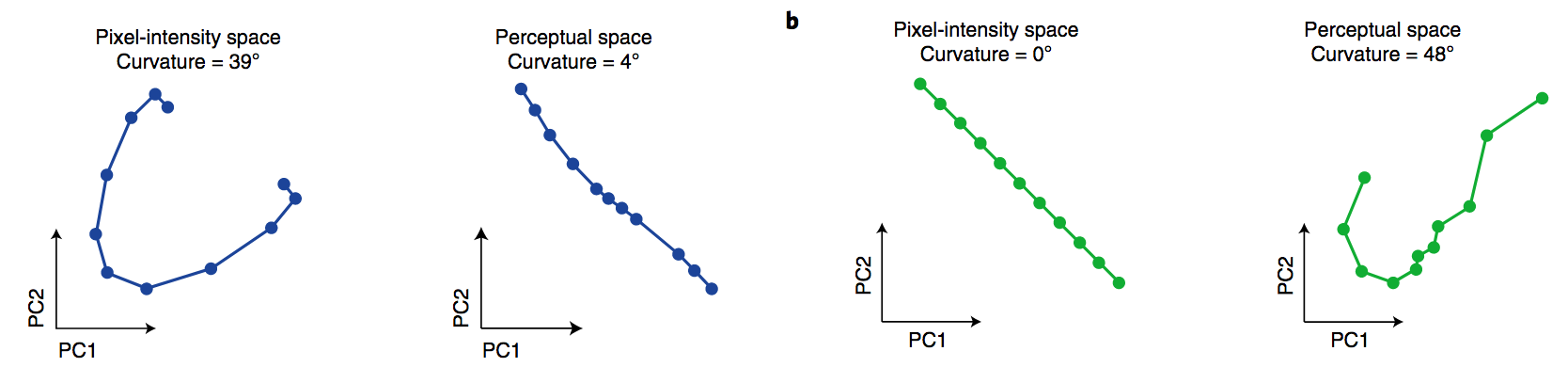

The main results of the paper - as expected - is that natural video sequences indeed appear to be mapped to straight trajectories in representation space. Furthermore, the figure below (Fig. 3b in the article) shows that the straightness of trajectories which correspond to natural stimuli is higher than the straightness of unnatural, artificially generated stimuli:

The blue curves correspond to a natural video stimulus in pixel space and in (inferred) representation space. You can see that the sequence is highly curved in pixel space, but in representation space it is straight. On the other hand, the green curves show an artificial video created by linearly interpolating between the first and the last frame of a video. This of course results in a straight trajectory in pixel space. However, the inferred trajectory in representation space is highly curved, which was the author's prediction as this is an unnatural stimulus for the human.

I really liked this paper and it is an excellent example of ideal observer model-based analysis of psychophysics data. It formulates an interesting hypothesis and finds a very nice way to answer it from well-designed experimental data.

That said, I was left wondering just how critically the results depend on assumptions of the ideal observer model, and how robust the findings are to changing some of those assumptions. For one, the paper assumes a Gaussian observation noise in representation space, and I wonder how robust the analysis would be to assuming heavy-tailed noise. Similarly, our very definition of straightness and angles relies on the assumption that the representation space is somehow Euclidean. If the representation space is not in fact Euclidean, our analysis might pick up on that, rather than the straightness of specific trajectories. That said, the most convincing aspect of the paper is contrasting natural vs unnatural stimuli. No matter how precise our inference of straightness is, and how much the actual values depend on changing these assumptions, this is a very reassuring finding.